“Marilyn, that icon of über-femininity, is most often compared to other dead women. Or rather, other dead women are compared to her … Whenever a glamorous young woman dies, she is compared to Marilyn Monroe, whether she was a blonde – or dumb – or not.” – Sarah Churchwell

“Like many women, I’ve been studying Marilyn Monroe my entire life,” Karina Longworth writes in the notes for her podcast, You Must Remember This. After making her name in the blogosphere, Longworth has published studies of contemporary movie icons including Meryl Streep.

No less than three classic Monroe films (Bus Stop, Some Like It Hot, and The Misfits) are featured in Hollywood Frame by Frame, a book of contact sheets for which Longworth supplied the text. Since 2014, she has been exploring Hollywood history in her popular and influential podcast. A trilogy of episodes about Marilyn’s life and death is the centrepiece of a dedicated series, ‘Dead Blondes’, and her marriage to Arthur Miller was profiled in an earlier season, ‘The Blacklist.’

In this pantheon of dead blondes, Marilyn is preceded by Peg Entwhistle, Thelma Todd, Jean Harlow, Veronica Lake and Carole Landis; and her successors include Jayne Mansfield, Barbara Payton, Grace Kelly, Barbara Loden and Dorothy Stratten. “The title is a little bit tongue-in-cheek, but it’s also incredibly literal,” Longworth told Entertainment Weekly. “There does seem to be this fascination in the wider culture with these quote-unquote ‘perfect victims,’ the beautiful woman who is taken too soon.”

The first episode, ‘Marilyn Monroe: The Beginning’, is also a repeat, from the ‘Star Wars’ season. Longworth retells the story of Norma Jeane’s unhappy childhood and rise to fame. While she certainly grew up in the shadows of Hollywood, Longworth’s deterministic view is probably overstated. Reframing old gossip from a postmodern perspective, she takes Marilyn’s rumoured promiscuity at face value, as a symptom of endemic sexual harassment. Her early films are barely mentioned, as Longworth believes that cheesecake photos (which suggested to men that Marilyn was “easily pleased,” although she actually found the whole process rather amusing), plus her deft handling of the nude calendar scandal, and a headline-grabbing romance with Joe DiMaggio played a greater part in her ascent to stardom. Mastering her own publicity, she became a “sex goddess for the people,” and by openly discussing her experiences of abuse, she projected a type of “female damage” that women understood all too well. But the guileless vulnerability which solidified her image soon became a prison.

The first episode, ‘Marilyn Monroe: The Beginning’, is also a repeat, from the ‘Star Wars’ season. Longworth retells the story of Norma Jeane’s unhappy childhood and rise to fame. While she certainly grew up in the shadows of Hollywood, Longworth’s deterministic view is probably overstated. Reframing old gossip from a postmodern perspective, she takes Marilyn’s rumoured promiscuity at face value, as a symptom of endemic sexual harassment. Her early films are barely mentioned, as Longworth believes that cheesecake photos (which suggested to men that Marilyn was “easily pleased,” although she actually found the whole process rather amusing), plus her deft handling of the nude calendar scandal, and a headline-grabbing romance with Joe DiMaggio played a greater part in her ascent to stardom. Mastering her own publicity, she became a “sex goddess for the people,” and by openly discussing her experiences of abuse, she projected a type of “female damage” that women understood all too well. But the guileless vulnerability which solidified her image soon became a prison.

In a decade characterised by material pleasures and sexual repression, curvaceous Marilyn represented ‘a feminine icon of plenty’, but in private, she was plagued by miscarriages and endometriosis. Ezra Goodman, in his The Fifty Year Decline and Fall of Hollywood, described her, and the blonde bombshells who followed in her wake, as ‘lost souls’ whose malleable personae mirrored post-war America’s identity crisis. In ‘Marilyn Monroe: The Persona’, Longworth focuses on her initial starring roles. She gave an affecting performance in Don’t Bother to Knock, an overlooked drama which Longworth judges “both terrifying and sympathetic in its sexualised portrait of female hysteria.”

This was followed by “a trilogy of parodies of consumerism”, starting with Niagara (1953), in which she plays the libidinous Rose, her only character to die onscreen. Although Rose is herself an accessory to murder, Longworth finds her death “legitimately sad – but sadness doesn’t sell.” After Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Marilyn would be more often identified with comedic parts. Lorelei Lee, Longworth argues, was “the smartest of [Monroe’s] dumb blondes”, justifying her lust for diamonds and manipulation of men as essential self-protection. Blondes was also her first major musical, in which, alongside co-star Jane Russell, she mastered “acting in song.” How to Marry a Millionaire took a more critical view of the selfish society, but is also less cynical as the gold-diggers finally choose love.

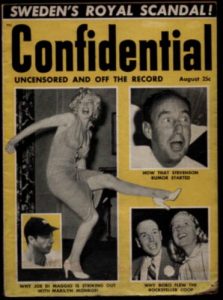

Media coverage of her career was often blatantly sexist, such as the 1953 Confidential article, ‘Why Joe DiMaggio Is Striking Out With Marilyn Monroe’, which alleged that movie mogul Joe Schenck was her ‘sugar daddy’. Some of her movies were also regressive in their gender politics, such as River of No Return (1954), in which her character falls for Robert Mitchum after an attempted rape. Even Bus Stop (1956), her first film under a new contract – in which, influenced by the Method, she gave one of her best performances – veers between “garish comedy” and a more sensitive exploration “a woman trying to direct her own life.”

Media coverage of her career was often blatantly sexist, such as the 1953 Confidential article, ‘Why Joe DiMaggio Is Striking Out With Marilyn Monroe’, which alleged that movie mogul Joe Schenck was her ‘sugar daddy’. Some of her movies were also regressive in their gender politics, such as River of No Return (1954), in which her character falls for Robert Mitchum after an attempted rape. Even Bus Stop (1956), her first film under a new contract – in which, influenced by the Method, she gave one of her best performances – veers between “garish comedy” and a more sensitive exploration “a woman trying to direct her own life.”

Longworth believes that incidents like the broken strap at Marilyn’s 1956 press conference with Sir Laurence Olivier were “highly calculated”, and by the time she was filming The Prince and the Showgirl in England, Olivier apparently shared that view. Newly married to Arthur Miller, and under the spell of the Strasbergs and psychoanalysis, Marilyn was also dependent on sleeping pills, and the doctors who prescribed them.

After their relationship went public, Arthur Miller was targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC.) He had attended a few Communist Party meetings in the 1930s, but by 1956, he was no longer interested in party politics. He later claimed that the chairman of HUAC had offered to drop the charges if Marilyn would pose for a photograph with him. She was also being monitored by the FBI at this time, and during filming of Bus Stop, they believed she was living at the Chateau Marmont. This was incorrect – her drama coach, Paula Strasberg, was staying at the hotel, although Marilyn may have used the suite for ‘trysts’ with Miller. As Longworth notes in ‘The Blacklist: After the Fall’, Paula had previously been named by Miller’s former associate, Elia Kazan, in his testimony before HUAC.

After their relationship went public, Arthur Miller was targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC.) He had attended a few Communist Party meetings in the 1930s, but by 1956, he was no longer interested in party politics. He later claimed that the chairman of HUAC had offered to drop the charges if Marilyn would pose for a photograph with him. She was also being monitored by the FBI at this time, and during filming of Bus Stop, they believed she was living at the Chateau Marmont. This was incorrect – her drama coach, Paula Strasberg, was staying at the hotel, although Marilyn may have used the suite for ‘trysts’ with Miller. As Longworth notes in ‘The Blacklist: After the Fall’, Paula had previously been named by Miller’s former associate, Elia Kazan, in his testimony before HUAC.

Miller famously did not ‘name names’, and was estranged from Kazan. By the time of his acquittal in 1958, Marilyn was filming Some Like It Hot. Her problems on the set are well-documented, but it would become her most enduringly popular movie. Playing the “dumbest of blondes”, Longworth remarks that she “had nothing ‘mental’ to work with.” Her next film, Let’s Make Love, was notable mainly for her affair with co-star Yves Montand. After hearing the gossip, Kazan approached Miller and they began working on After the Fall, a play which draw heavily on his troubled marriage, and would open at the Lincoln Center, which the two men co-founded, in 1964.

The Misfits, which Miller wrote for Marilyn, is one of Longworth’s favourite movies – although she criticises him for “lazily and cruelly” incorporating scenes from their marriage into the script. Nonetheless, Marilyn’s training in the Method suited the introspective material. From Some Like It Hot onwards, Longworth argues, Marilyn’s screen persona was becoming more natural and poignant. After divorcing Miller, she depended increasingly on her psychiatrist, Dr Ralph Greenson. Longworth sees this as a controlling relationship, and observes in ‘Marilyn Monroe: The End’ that he failed in weaning her off prescribed drugs. Concluding that there is little agreement between scholars and investigators on Marilyn’s rumoured affairs with the Kennedy Brothers, Longworth believes that her “sad, but not dramatic” demise was probably accidental, and to those who knew the scale of her addiction, even inevitable.

The Misfits, which Miller wrote for Marilyn, is one of Longworth’s favourite movies – although she criticises him for “lazily and cruelly” incorporating scenes from their marriage into the script. Nonetheless, Marilyn’s training in the Method suited the introspective material. From Some Like It Hot onwards, Longworth argues, Marilyn’s screen persona was becoming more natural and poignant. After divorcing Miller, she depended increasingly on her psychiatrist, Dr Ralph Greenson. Longworth sees this as a controlling relationship, and observes in ‘Marilyn Monroe: The End’ that he failed in weaning her off prescribed drugs. Concluding that there is little agreement between scholars and investigators on Marilyn’s rumoured affairs with the Kennedy Brothers, Longworth believes that her “sad, but not dramatic” demise was probably accidental, and to those who knew the scale of her addiction, even inevitable.

Karina Longworth is an accomplished storyteller and perceptive critic, but her research is not impeccable. Her main sources are biographies by Donald Spoto, Gloria Steinem and Lois Banner. Although she takes a mostly sympathetic, even feminist view, she is not immune to sensationalism and once posted – but later deleted – Marilyn’s autopsy photo on Twitter to promote the show (it was first published, amid much disquiet, in Anthony Summers’ Goddess.) She occasionally misattributes quotations, or conflates different events, which can give a misleading impression. For example, while the young Norma Jeane may have fantasised that her father was Clark Gable, there is no evidence that she actually believed this, or told it to others. And the 113-ft ‘longest walk in history’ in Niagara was not Marilyn’s death scene. If Longworth’s aim is to demythologise the Monroe legend, she doesn’t fully succeed. Although You Must Remember This offers a lively analysis of the star system, it shouldn’t be taken too literally but rather as a starting point for further exploration.

Tara Hanks for Immortal Marilyn