Murder Orthodoxies: Sex, Lies and Marilyn

Among the thousand or more books about Marilyn Monroe, there are certain strands – from coffee-table monographs to cultural criticism. One theme is so persistent, however, that it has become a sub-genre in its own right. Armed with dubious confessions and conspiracy theories, their authors argue that Marilyn’s untimely death was the result of foul play in high (and low) places, and these allegations have been seized upon by readers, as well as journalists and documentarians.

A handful of writers have directly challenged these assumptions. In 2005, David Marshall collected the findings of some dogged fans in The DD Group: An Online Investigation Into the Death of Marilyn Monroe. More recently, the internet radio show Goodnight Marilyn has featured input from psychotherapist and Monroe fan-turned-biographer, Gary Vitacco-Robles, and forensic pathologist Dr Cyril Wecht.

First-time author Donald McGovern follows in their footsteps with Murder Orthodoxies: A Non-Conspiracist’s View of Marilyn Monroe’s Death, a rigorous excavation of the myths and legends, meticulously structured and packed with intricate detail over 566 pages.

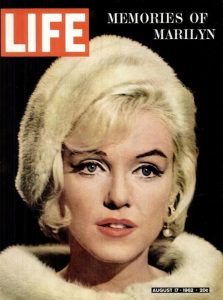

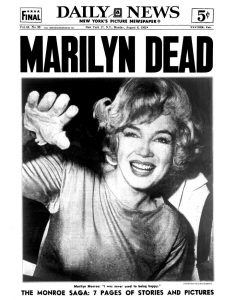

It all began at Madison Square Garden on May 19, 1962, when Monroe sang ‘Happy Birthday, Mister President’ to John F. Kennedy as hundreds of well-wishers looked on. Among them was gossip columnist Dorothy Kilgallen, who described this sensuous performance as a literal seduction. Less than three months later, Marilyn took a fatal overdose of barbiturates, and died alone in her bed.

It all began at Madison Square Garden on May 19, 1962, when Monroe sang ‘Happy Birthday, Mister President’ to John F. Kennedy as hundreds of well-wishers looked on. Among them was gossip columnist Dorothy Kilgallen, who described this sensuous performance as a literal seduction. Less than three months later, Marilyn took a fatal overdose of barbiturates, and died alone in her bed.

That September – as noted by Monroe biographer Donald Spoto – three men met in Los Angeles to discuss Hollywood’s communist problem. Those men were Frank Capell, editor of a right-wing newsletter, Herald of Freedom; Maurice Ries, head of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals; and Jack Clemmons, a Los Angeles police sergeant who had been the first to arrive at Marilyn Monroe’s house after her death was reported. All three were vehemently opposed to the Kennedy administration; and according to Ries, the president’s brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, had been Monroe’s lover.

Capell relayed this story to columnist Walter Winchell, who was close to Marilyn’s ex-husband, Joe DiMaggio. Winchell had been a staunch Monroe fan until 1955, when she divorced Joe and met her third husband, playwright Arthur Miller, who would be soon investigated by the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee. Even after the couple separated, Marilyn’s liberal associations were followed with some interest by the Bureau’s long-time head, J. Edgar Hoover.

Over the next year or so, Winchell published snippets of innuendo about Marilyn in his column, fed to him by Capell. After John F. Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, the red-baiters’ attentions turned to Bobby, who was contemplating a Senate run. Several months later, Capell produced a short pamphlet implicating the younger Kennedy in The Strange Death of Marilyn Monroe. It drew little interest, and by 1968 Bobby was also dead, while Capell and Clemmons had been disgraced for their part in a plot to defame another politician.

The rumours should have ended there, but in 1973, the novelist Norman Mailer dropped some of Capell’s insinuations into his ‘factoid’ biography, Marilyn. A year later, hack reporter and small-time film producer Robert Slatzer took up where Mailer left off with The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe. And in the age of Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon, the scandal that began as a political smear suddenly became a media goldmine.

The rumours should have ended there, but in 1973, the novelist Norman Mailer dropped some of Capell’s insinuations into his ‘factoid’ biography, Marilyn. A year later, hack reporter and small-time film producer Robert Slatzer took up where Mailer left off with The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe. And in the age of Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon, the scandal that began as a political smear suddenly became a media goldmine.

In 1982, the allegations that Marilyn had been murdered (at the behest of the Kennedys, by the Mafia, or CIA) were reviewed in a threshold investigation by the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office. No credible evidence of homicide was found, but this only served to fuel the fire. In 1985, Anthony Summers published his blockbuster, Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe, relying heavily on the testimony of Slatzer, Jeanne Carmen (Marilyn’s self-professed ‘best friend’); and Senator George Smathers (a former friend of the late president.)

Summers’ bestseller spawned several other conspiracy volumes, including Crypt 33 by the private investigator and self-publicist, Milo Speriglio; Double Cross by Chuck Giancana, putting his mobster brother Sam in the frame; and a salacious memoir by would-be actor Ted Jordan, who declared himself Marilyn’s lifelong lover and claimed to be in possession of her ‘red diary’, previously mentioned by his rival for the spotlight, Bob Slatzer. Another celebrity P.I., Fred Otash, claimed he had wiretapped Marilyn’s house and helped to ‘sweep’ the property of incriminating evidence after her death.

In Victim (2004), Matthew Smith featured extracts from alleged tapes made by Marilyn before her death to psychiatrist Dr. Ralph Greenson. Rather like the red diary, those recordings have never been located; but John Miner, an attorney who had attended Monroe’s autopsy, claimed to have heard them. His mooted transcript was published in full a year later in the Los Angeles Times. Lionel Grandison, another peripheral figure, reimagined the ‘red diary’ in Memoir of a Deputy Coroner (2013), arguing that Marilyn was a secret government agent.

Other popular conspiracy books, such as Donald Wolfe’s The Assassination of Marilyn Monroe (1998) and Jay Margolis and Richard Buskin’s The Murder of Marilyn Monroe: Case Closed (2014), have fused various murder theories, including the rumour that Dr. Greenson was yet another of Marilyn’s lovers – and also her killer. A common thread, first proposed by Slatzer, was that she had threatened to hold a press conference disclosing her affairs with the Kennedys, and matters of national security (including, according to some ufologists, her knowledge of the alien landings at Roswell.)

Other popular conspiracy books, such as Donald Wolfe’s The Assassination of Marilyn Monroe (1998) and Jay Margolis and Richard Buskin’s The Murder of Marilyn Monroe: Case Closed (2014), have fused various murder theories, including the rumour that Dr. Greenson was yet another of Marilyn’s lovers – and also her killer. A common thread, first proposed by Slatzer, was that she had threatened to hold a press conference disclosing her affairs with the Kennedys, and matters of national security (including, according to some ufologists, her knowledge of the alien landings at Roswell.)

During the final months of her life, Marilyn was embroiled in a bitter legal battle with her studio; she was having daily sessions with Greenson, and relying on large doses of sleeping pills from her physician, Dr. Hyman Engelberg. She had suffered from depression for most of her life, and had a history of overdoses and suicide attempts. She may have met John and Robert Kennedy on just four occasions; their daily itineraries are in the public domain, and her routine is also well-documented. Only one sexual encounter with the president can be reasonably ascertained. Whatever her private demons, Monroe would surely have realised that such an indiscretion would end her career. Her own sporadic journal entries (collected in the 2010 book, Fragments) contain no references to either Kennedy.

McGovern looks finally to her autopsy report, compiled by renowned pathologist Dr. Thomas Noguchi, for the true cause of her death. As a long-time drug user, Marilyn had a high tolerance which enabled her to ingest multiple pills in succession. Conspiracists have pointed to the disposal of some organs as proof of a cover-up, but as Noguchi pointed out, the toxicologist’s analysis of her liver and blood samples made further tests unnecessary.

With dry wit and exhaustive scrutiny, McGovern exposes the insupportable and absurd aspects of what has nonetheless become an urban myth. McGovern’s book will not, of course, be the last word on the subject; but it offers a timely redress to decades of shallow sensationalism. And in an era when ‘fake news’ is poisoning the fabric of public life, McGovern’s systematic unravelling of the calculated distortions that have so clouded Monroe’s legacy provides us with a very modern cautionary tale.

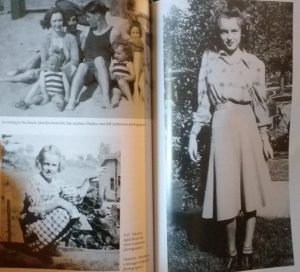

That’s an entirely different question. Marilyn Monroe came into adulthood in the era when women went to work to step up for the war effort. And she didn’t wait around for her husband to return; a taste of independence and freedom sent her instead into her first divorce and the long, hard fight for a career in Hollywood.

That’s an entirely different question. Marilyn Monroe came into adulthood in the era when women went to work to step up for the war effort. And she didn’t wait around for her husband to return; a taste of independence and freedom sent her instead into her first divorce and the long, hard fight for a career in Hollywood. Of Women and Their Elegance

Of Women and Their Elegance How do you solve a problem like Norma Jeane, when even her name is in doubt? More than a thousand books to date have been devoted to this question. As Ezra Goodman, at the height of her fame, wrote so prophetically: “The riddle that is Marilyn Monroe has not been solved.” Andrew Norman’s

How do you solve a problem like Norma Jeane, when even her name is in doubt? More than a thousand books to date have been devoted to this question. As Ezra Goodman, at the height of her fame, wrote so prophetically: “The riddle that is Marilyn Monroe has not been solved.” Andrew Norman’s  Compounding her sense of abandonment was the spectre of sexual abuse. Returning to

Compounding her sense of abandonment was the spectre of sexual abuse. Returning to

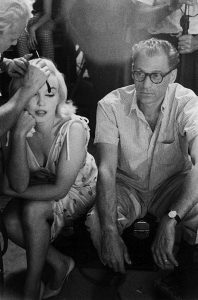

Behind the scenes, Miller was alarmed by her psychological dependence on acting coaches Lee and Paula Strasberg, and her growing addiction to sleeping pills. Watching Marilyn perform ‘I’m Through With Love’ in

Behind the scenes, Miller was alarmed by her psychological dependence on acting coaches Lee and Paula Strasberg, and her growing addiction to sleeping pills. Watching Marilyn perform ‘I’m Through With Love’ in

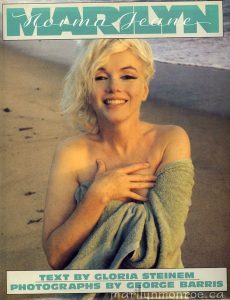

Marilyn: Norma Jeane

Marilyn: Norma Jeane

The first episode, ‘

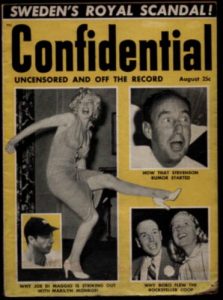

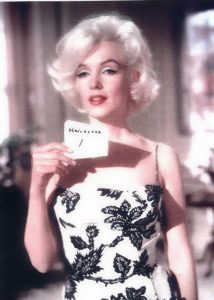

The first episode, ‘ Media coverage of her career was often blatantly sexist, such as the 1953

Media coverage of her career was often blatantly sexist, such as the 1953  After their relationship went public, Arthur Miller was targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC.) He had attended a few Communist Party meetings in the 1930s, but by 1956, he was no longer interested in party politics. He later claimed that the chairman of HUAC had offered to drop the charges if Marilyn would pose for a photograph with him. She was also being monitored by the FBI at this time, and during filming of

After their relationship went public, Arthur Miller was targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC.) He had attended a few Communist Party meetings in the 1930s, but by 1956, he was no longer interested in party politics. He later claimed that the chairman of HUAC had offered to drop the charges if Marilyn would pose for a photograph with him. She was also being monitored by the FBI at this time, and during filming of  The Misfits

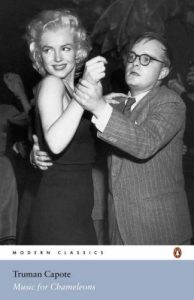

The Misfits But what does this have to do with Marilyn? Simple. A collection of his essays issued in 1980 includes a piece called “A Beautiful Child”, a small memory work that focuses on the afternoon he and Marilyn spent together following Constance Collier’s funeral in April 1955. April 28, 1955 to be exact, as he informs the reader in the very first line.

But what does this have to do with Marilyn? Simple. A collection of his essays issued in 1980 includes a piece called “A Beautiful Child”, a small memory work that focuses on the afternoon he and Marilyn spent together following Constance Collier’s funeral in April 1955. April 28, 1955 to be exact, as he informs the reader in the very first line.