1953

Dover Publications is a US company, founded in 1941, that reissues classic literary works in value-priced, paperback editions. In 2010, Dover broadened their remit by publishing ‘Marilyn, August 1953: The Lost Look Photos’, a hardback, coffee-table book featuring John Vachon’s photographs of Marilyn Monroe in Canada, while filming ‘River of No Return’, most of which had never been seen before. It was released under their Calla Editions imprint, using paper from sustainable forests, and presented in landscape format. On the grey front cover, under the dust jacket, is a silhouette of Monroe.

John Vachon was born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, in 1914. His surname is French-Canadian, but his father was Irish. The Vachons were not well-off, but John’s mother encouraged him to pursue his education. He graduated from his hometown’s University of St Thomas in 1934. His plans to write or teach were dashed, though, when his graduate scholarship was withdrawn after a drinking binge.

He was married to Millicent Leeper, known as ‘Penny’, four years later. In 1935, Vachon had moved to Washington where he found work as a filing clerk at the Farm Security Administration, established at the height of the Great Depression by President Roosevelt, as part of the historic ‘New Deal’. One of the FSA’s lasting legacies was cultural: the photography program of 1935-44 revealed startling images of poverty-stricken, rural America to the world.

Vachon became passionately interested in photography. “Vachon’s job as a file clerk since 1937 had allowed him access to the thousands of photographs they had produced, and he prided himself on the highly organised archival system he established to file and retrieve these images,” writes Brian Wallace, in his introduction to ‘The Lost Look’. “Vachon, who had been raised in rural Minnesota, was especially drawn to the version of small-town America depicted in Walker Evans’ photographs.”

In fact, Vachon’s early work was strongly influenced by Evans. But Vachon belonged to the ‘second generation’ of FSA photographers, whose emphasis was by then less focussed on rural deprivation than on urban conditions and the gradual encroachment of World War II on the American people. Now that the Depression was receding, photographers like Vachon were allowed the freedom to pursue more personal projects.

A few of Vachon’s FSA pictures are included in ‘The Lost Look’, most notably ‘Farm Girl, Seward County, Nebraska’ (1938.) As Brian Wallis notes, this photo “encapsulates like a novel all the wanderlust and dreams and damaged innocence of an isolated rural schoolgirl.”

On the road, Vachon liked to read James Joyce, kept a daily journal and wrote long, pithy letters home to his wife. Always an introvert, Vachon was nonetheless a risk-taker and drank heavily throughout his life. Above all, Vachon insisted that his work should have “feeling,” which he defined as “the humourlessness, the pity, the beauty of the situation.”

But in the post-war era, the bulk of employment for photographers like Vachon was with glossy, large-format magazines, such as ‘Life’ and ‘Look’. Managed by the famous husband and wife team, Gardner and Fleur Cowles, ‘Look’ had a slightly smaller circulation than ‘Life’, but it boasted a wider scope of features and respected writers. In 1947, Vachon was hired as a staff photographer.

“At ‘Look’ you work with a writer and it really is a team sort of thing,” Vachon explained. “We talk a lot about the story before we go on it, and while we’re there, we know what we want to say, and we’re doing a story.” This approach was very different to the realist style of the FSA. “I’m known at ‘Look’ as the photographer who can’t do so well in a purely set up and directed story,” Vachon admitted, “and I’m usually sent on things which require my seeing what’s there rather than arranging what’s there, so I’d say that’s perhaps the influence that stayed with me.”

RIVER OF NO RETURN

Vachon arrived in Banff, Alberta, while Marilyn was recuperating from an accident. He wrote to his wife, Penny, on August 14, regarding Stanley Rubin, producer of ‘River of No Return’: “I could see from today’s tour that we won’t be able to really work together at all,” Vachon told Penny after meeting Rubin, who had arranged the shoot with the editors of ‘Look’, on August 15. “He’ll be sweet and agreeable, but all his picture ideas are terribly flat and dull and embarrassing.”

With Monroe still holed up in her hotel room, it seemed that Vachon’s concerns were justified. “I am just totally confused, by the myriad publicity people, production people, and all that I’ve been meeting all day and not understanding,” he confessed on August 16, adding, “I had to come to Banff to learn to really hate Hollywood.” The chaotic atmosphere is typified by a conversation Vachon overheard at the Banff Springs Hotel. “Tonight two white-haired old ladies like your aunts rode down the elevator with me,’ he wrote to Penny on August 18, “and one said, ‘Where shall we eat? I don’t want to cope with that Marilyn Monroe.’ Marilyn hadn’t been near the dining room.”

On August 19, Marilyn was still “incommunicado.” However, her hairdresser and make-up man invited Vachon to photograph Marilyn with Joe DiMaggio in their hotel suite. “There will doubtless be 40 people in that room tomorrow when I go in to take some intimate candid pictures,” Vachon complained. “I am pretty unhappy that I won’t have a chance, apparently, to really work on Monroe.”

On the night of Thursday, August 20, John Vachon was finally allowed to photograph Marilyn. “And 2 hours in Marilyn’s suite this afternoon – a very interesting girl,” he wrote to Penny. “She’s real different from any pre conception,” he added, “just a friendly girl, not especially sexy, as they say, kind of sweet and dumb. Obviously crazy in love for this DiMaggio fellow. He was okay, too…”

While the Hollywood machine drove Vachon to distraction, Monroe was a gifted, graceful model, more at home before the still camera than with directors like Preminger. Given Vachon’s frank disdain for Hollywood, I think we can take his description of Marilyn as an “interesting girl” to be a sincere compliment.

PICTURES OF THE MOVIE QUEEN

The first pictures that Vachon took were of Marilyn and Joe DiMaggio, sitting on a window ledge, overlooking a mountain range. Monroe and the retired baseball player had been dating for over a year, and he had flown to Canada when he heard of her injury. After more than a decade in the spotlight, DiMaggio was tired of publicity. But Monroe’s star was rapidly rising, and it was indeed a coup for Vachon to secure a formal photo session with the famous couple.

In these pictures, Marilyn seems girlish and unaffected. For his part, DiMaggio looks more relaxed than usual. In one shot, Monroe playfully licks her lips, and in another she nuzzles, catlike, with Joe. The session seems to epitomise a moment in time when she was free to bask in his protective love. ‘In each frame,’ Brian Wallis observes, “DiMaggio looks adoringly at Monroe…”

After an hour, Joe left and Vachon was able to photograph Marilyn alone. She looks surprisingly demure and fresh-faced. As Wallis notes, these candid shots show off Monroe’s “uncanny ability to change moods subtly while posing for the camera,” and Vachon’s “great skill at using natural illumination.”

Marilyn is kittenish one moment, introspective the next. In another sequence, Vachon shoots her from above. She seems nervous, perhaps conscious of the cast on her leg. The shadows behind her suggest, as Wallis notes, “the melodramatic menace of a contemporary B-movie or film noir.”

Attempting to lighten the mood, Vachon handed Marilyn a prop: an outdated ‘stick’ telephone. She rose to the comic potential of the situation, and even allowed Vachon to take candid shots after the formal poses were done. It seems clear that by the end of their first session, photographer and model had established a rapport.

Three days later, on August 22, Vachon photographed Marilyn again. Wearing a dark bikini, Marilyn posed poolside at Stanley Rubin’s suggestion. One is struck by how slender she was, but her plaster cast and crutches make the scenario ridiculous. Though eager to please, Marilyn could not hide her boredom. Eventually, Vachon gave up and they are photographed together, laughing like naughty children at the absurdity of their task.

The following sequence is by an outdoor pool, with a pouting Marilyn dipping her bandaged leg in the water (with a stiletto on the other foot.) She seems to be spoofing her own predicament, and perhaps gently mocking the Hollywood moguls who had inadvertently caused it. This was the first of many acts of rebellion by the allegedly meek starlet.

Dressed in a tight-fitting sweater and skirt, Marilyn embarked on the next stage of her assignment, entitled ‘Hollywood Comes to Canada,’ She poses obediently before the ‘Welcome to Banff’ sign, and then wraps herself provocatively around a rather phallic-looking post. Again, there is a sense that both Monroe and Vachon were working together to fulfil their employers’ remit, but also to subvert it.

Monroe’s bold sensuality had defined her appeal, but it also made her ‘too hot to handle’ in the conservative climate of 1950s America. Perhaps this is why she was so often cast in ‘dumb blonde’ roles, where her sexuality was no longer threatening, but a kind of joke. However, in her work as a model, Marilyn was free to collaborate with photographers to produce memorable, enticing images.

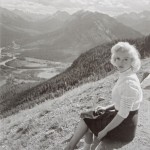

Whether riding in a chairlift, or waiting or crutches to be made up, Monroe was both patient and co-operative, the antithesis of the ‘difficult’ reputation she would soon acquire on film sets. As she sits on the mountain, those mercurial moods flicker across her face yet again, and we are left to marvel at this stunning blonde bombshell, alone with nature.

More props, and more contrivances were added. Marilyn poses in the arms of a stuffed bear, looking up fearfully. This corny premise is realised because she appears so truly helpless, and yet there’s a twinkle in her eye. She mirrors the stiff posture of a Canadian Mounted Policeman, then giggles as she pins a badge on his shirt.

She steers a canoe, plays golf, and lies down on a white bearskin rug. Monroe was nothing if not inventive and here, as in much of her best work, her generosity and childlike energy seem boundless. A final sequence shows Marilyn behind the camera, and one of these shots graces the book’s front cover. This reflects that Monroe was, in her own way, as much an artist as Vachon himself.

SIXTY YEARS LATER

It is almost sixty years since that summer in Canada when John Vachon photographed Marilyn Monroe. After returning to Los Angeles in September, Marilyn posed for another ‘Look’ photographer, Milton Greene. The results were extraordinary, and Greene was sympathetic to Monroe’s creative aspirations. Within a year, she had hired Greene as her business partner.

Meanwhile, Vachon’s pictures were relegated to a short article near the back of an October issue, under the headline, ‘Location Loafing.’ The cover stars that week were a quarterback and a cheerleader from the University of Minnesota. The majority of Vachon’s photos of Marilyn have remained unpublished until now. However, a portrait of Marilyn smoking a cigarette, taken by Milton Greene, made ‘Look’’s cover in November.

‘River of No Return’ was released in April 1954, and by then Monroe and DiMaggio were married. She had turned down her next movie and been suspended by the studio. In a few more months, the marriage would falter, and Monroe would abandon Hollywood for New York. The gamble paid off, but the price she paid was dear – in her final years, Monroe won the freedom she craved, but her personal life was often turbulent.

“A Grade Z cowboy movie in which the acting finished second to the scenery and the Cinemascope process,” is how Marilyn described ‘River of No Return’. However, in a closing essay for ‘The Lost Look’, John Grafton argues, “It was a plateau near the peak of her Hollywood career – the bad years and the cruel descent down the other side of the mountain turned out to be just around the corner. No one would have believed it possible…Whatever its limitations as a movie, no matter how relentlessly it embodied all the clichés of the Hollywood Western in the 1950s, ‘River’ was then, is now, and always will be Marilyn at her most intoxicating.”

Vachon went on to photograph many other celebrities, including Nikita Khrushchev, John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. His wife, Penny, suffered from depression and tragically committed suicide in 1959. Vachon married Françoise Fourestier two years later.

He continued working for ‘Look’ until 1971, covering hundreds of stories. One editor dubbed him “our poet photographer.” Vachon continued to work as a freelance photographer, and in 1975, he was appointed a visiting lecturer at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Sadly, he died of cancer in New York later that year, aged 60.

“Vachon faced his own death with great courage,” his friend and co-writer, Thomas B. Morgan, recalled in a 1989 issue of ‘American Heritage’ magazine. “But again he seemed almost bemused by his suffering and was going gently. I saw him at home a few days before he died…He had come to terms with his death, I think, but perhaps not yet with his life. He had always had a sense of humor; but there was no soul-searching talk in him. He had depended on his friends to protect him, and the rage in him just never came out.”

“Although Vachon succeeded as a journalist, fame and fortune passed him by,” Morgan reflected. “He was better known in life as a member of the FSA project than as one of Look’s stars. In public he was a quiet man, shy to the point of disability in a world that often rewards self-promoters. In private he often seemed to be faintly smiling to himself as though life had just taken a swing at him and missed.”

Christine Vachon, his daughter by his second marriage, is an independent film producer, with Oscar-winning films like ‘Far From Heaven’ and ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ to her credit. She is currently working on the HBO mini-series, ‘Mildred Pierce’, with Kate Winslet in the title role.

‘Marilyn, August 1953: The Lost ‘Look’ Photos’ is a must-have for dedicated Monroe fans, though casual readers might prefer a more general pictorial. Some of the pictures are rather small, and parts of the text are repetitive, but overall it is a fine tribute. It is also a visual feast for students of photography, and shows a more light-hearted side of Vachon. A selection of his other work is published in another recent book, ‘The Photographs of John Vachon.’

Vachon only worked with Monroe once, and this represents a unique stage in her career. Her hair is long and coiffed, in the style that Jayne Mansfield would later imitate. But Monroe was eager to discard the ‘pin-up’ caricature, and for most of her subsequent career, her hair was kept short. In his introductory essay, Brian Wallis remarks on the dichotomy between the glamour of Monroe and Vachon’s naturalistic style, which made their collaboration so intriguing. “It is this improbable combination of extreme stylisation and unexpected sweetness that typifies Monroe’s enduring appeal. Indeed, in the 1980s, when Cindy Sherman and Madonna emulated Monroe’s stereotypical poses, it was precisely this stagy performance of threatened innocence that they reproduced. But, in fact, Monroe’s great skill as a performer was to deflect attention from the artifice – exaggerated as it was – and present herself as completely guileless and available.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]