1955

1956

1960

1961

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″ animation=”none” column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″][vc_column_text]MARILYN & EVE ARNOLD

“I have been poor and I wanted to document poverty; I had lost a child and I was obsessed with birth; I was interested in politics and I wanted to know how it affected our lives; I am a woman and I wanted to know about women.”

The pioneering photo-journalist, Eve Arnold, died on January 4th, 2012, at a London nursing home, three months short of her centenary.

She was born in Philadelphia on April 21, 1912, the seventh of nine children. Her father, William Cohen, was a Rabbi. He and his wife, Bessie, had come to America to escape anti-semitic persecution in Russia. Though well-educated, he could only find work as a pedlar, and Eve grew up in poverty.

She had planned to study medicine. But while Eve was working as a bookkeeper for a New York estate agent during World War II, a boyfriend gave her a Rolleicord camera. In 1943, she answered a newspaper ad asking for an ‘amateur photographer’, and became manager of America’s first automated film processing plant, in Hoboken, New Jersey.

Apart from a six-week course at the New School for Social Research, taught by Alexey Brodovitch, art director at ‘Harper’s Bazaar’, who taught her the basics of style and composition, along with unsparing critiques from the likes of Richard Avedon, Eve had no formal training and spent the rest of her life ‘learning by doing’.

Her first assignment was in 1950, covering fashion shows that took place daily in Harlem’s deconsecrated churches. “She found her way backstage to try to take more discreet pictures, hoping that the people working there would be too busy to notice her,” Brigitte Lardinois wrote in ‘Eve Arnold’s People’ (2009.) “This was a very novel way of photographing fashion; in those days fashion was all about posing in a studio, in a carefully controlled environment, while Eve was pursuing an exercise in pure photo reportage.”

America was still heavily segregated in 1950, and mainstream magazines seldom featured black people. However, Eve’s photos were syndicated throughout Europe. Unhappy with the snide captioning in Britain’s ‘Picture Post’, she vowed that all her pictures should henceforth speak for themselves.

In 1951, she approached Magnum Photos, the co-operative established four years previously by Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. At around the same time, Inge Morath joined Magnum’s Paris office. Together, they became the agency’s first female photo-journalists.

“Eve called Magnum a family – where ‘you love them all but you don’t necessarily like them all,’” Lardinois wrote. “Bresson taught her how to tell a story in a single definitive image…From Inge Morath she learned how to introduce lightness into her photographs; Ernst Haas taught her about colour; and Erich Hartmann taught her technical restraint and discipline. She discussed storylines with Burt Glinn and Dennis Stock. And she credits Elliott Erwitt with showing her how humour works in photography.”

“I met Eve Arnold at the beginning of my career,” Erwitt recalled. “At that time, married and with a young son, Eve was essentially a home-maker – a Long Island housewife and mother living in the village of Port Jefferson baking very good cookies.” Erwitt added that for Eve, photography “may have been a way to overcome the tedium of domesticity.”

Arnold later complained of being constantly offered second-rate, ‘women’s page’ assignments. “Magnum was a macho culture when Eve started there,” Mary Panzer, former curator of Washington’s National Portrait Gallery, told the ‘Los Angeles Times’.

Eve had married Arnold Arnold, an industrial engineer, in 1948. It was he who, in 1951, suggested that Eve cover the thousands of black southerners who had travelled north to work long, low-paid hours harvesting crops, and slept in crowded, ramshackle camps in Suffolk County, Long Island.

“If a photographer cares about the people before the lens and is compassionate, much is given,” Eve wrote later. “It is the photographer, not the camera, that is the instrument.”

Photographer Mary McCartney admires Eve’s portrait of a melancholy prostitute leaning on the bar of a Havana brothel in 1954. “You get a sense of her vulnerability – you feel that her life has been difficult, but that Eve is not judging her,” McCartney observed.

However, Eve failed to win over at least one tough-minded critic. When her photos of the first five minutes of a baby’s life were published in ‘Life’ magazine in 1954, Eve’s mother, Bessie, asked, “What’s to admire?”

MEETING MARILYN

Eve had her first experience of working with a movie star when she photographed Marlene Dietrich during a recording session, for ‘Esquire’, the upmarket men’s magazine. Some time later, Eve met Marilyn at a party given by John Huston at Manhattan’s 21 Club. “Marilyn asked – with that mixture of naïveté and self-promotion that was uniquely hers – ‘If you could do that well with Marlene, can you imagine what you could do with me?’” Arnold has recalled.

“At this time, she was a starlet and still relatively unknown,” Eve continued. “She had just appeared in a small part in ‘The Asphalt Jungle’.” That movie, directed by Huston, was released in 1950. (It may well be the case that Eve first met Marilyn shortly after, as they were introduced to each other by photographer Sam Shaw, Marilyn’s friend since 1951. However, the Dietrich story was published in 1952, by which time Marilyn was becoming a household name.)

EAST OF EDEN

Eve’s earliest photos of Marilyn were taken at the premiere of ‘East of Eden’ at New York’s Astor Theatre in March 1955. One shows her being interviewed by a female reporter for NBC. Over the previous five months, Monroe had separated from her husband, Joe DiMaggio, abandoned her film contract and moved to New York, where she established a production company with photographer Milton Greene.

The premiere was a benefit for the Actor’s Studio, and Marilyn was present as a ‘celebrity usherette’. “Although she was to me consistently beautiful,” wrote super-fan James Haspiel, who was outside her hotel when she left for the theatre, “there were few moments, this being one of them, when Marilyn looked so outrageously gorgeous that it was actually hard to look at her…She went onto the premiere, and the word quickly spread throughout Times Square that ‘Marilyn Monroe is over at the Astor Theatre!’ Soon people in the thousands picked up that information along Broadway.”

BRINGING ART TO THE MASSES

In early August of 1955, Marilyn – a lifelong insomniac – telephoned Eve in the dead of night. She was flying out next morning to Bement, Illinois, a town where her idol, Abraham Lincoln, had stayed in 1858, during a famed series of debates with Senator Stephen Douglas.

“I’m going to bring art to the masses,” Marilyn said. She wrote a speech about Lincoln on the plane to Chicago, and rehearsed it with her hairdresser, Peter Leonardi, and Eve, who remarked, “As she whispered the words of the talk about ‘our late, beloved President,’ it sounded like Eisenhower, not Lincoln, had just died.”

After a stopover in Chicago, they were driven to Champaign, and then taken by automobile cavalcade with the governor’s own motorcycle escort to Bement. The local media was alerted and chaos ensued.

By the time they reached Bement, Marilyn was exhausted. After a short rest, she was ready to face her public: she judged a group of bearded men in a Lincoln lookalike contest, admired the few pieces of art on display at Bryant Cottage, and finally, gave her speech.

Another round of interviews followed. Eve’s photographs of this eccentric junket are touching and funny. A demure, elegant Marilyn greeted each well-wisher, young and old, rich and poor, with unaffected warmth.

“She would watch the person photographing her – even if it was just a small-town newsman,” Eve observed. “She had learned that frequently the national press picks up from local wire services and she would perform at her best for all. With me she started to let down just to get a break, but if she sensed that I wanted more from her, she gave it in good measure.”

ULYSESS AT LONG ISLAND, 1955

Eve arranged to meet Marilyn again shortly after the jaunt to Bement, but on the appointed day, she left her camera at home. However, informal snapshots exist from that day, when Marilyn and her poet friend, Norman Rosten, walked along the beach near Eve’s home in Miller Place, Long Island. (Arnold dated this event back to 1952, but Marilyn didn’t meet Rosten until 1955.)

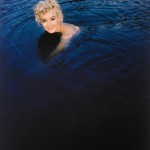

The vision of MM in a bathing suit soon drew onlookers. She played softball with Eve’s young son, Francis, and went for a swim with Rosten. “As she started to swim, her crowd of admirers followed suit and surrounded her,” Eve wrote later. “For a moment it looked as though they would drown her, they were so tightly packed around her.”

Happily, Marilyn was rescued. They met again soon after, as MM was visiting the Rostens over Labor Day weekend (traditionally the first in September.) To avoid another circus, Eve took Monroe to an abandoned children’s playground near Mount Sinai, Long Island.

Marilyn brought along three bathing suits, and a copy of James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’. “I asked her what she was reading when I went to pick her up (I was trying to get an idea of how she spent her time),” Eve remembered. “She kept ‘Ulysses’ in her car and had been reading it for a long time. She said she loved the sound of it and would read it aloud to herself to try to make sense of it–but she found it hard going. She couldn’t read it consecutively. When we stopped at a local playground to photograph she got out the book and started to read while I loaded the film. So, of course, I photographed her.”

The resulting pictures have graced endless book and magazine covers (especially if the topic is summer reading.)

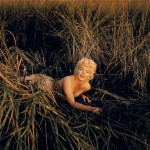

It was almost 5 pm – ‘the magic hour’, when the day is at its most golden. They drove on to deserted marshland. “The timing for the marshes was just right,” Eve noted, “the light soft and shadowless and ranging from pale yellow through deep saffron.”

Marilyn changed into a one-piece with a leopard-skin print. “The idea of the leopard in the bulrushes appealed to her sense of comedy,” Eve remarked. “She was intrepid. She stood in (the swamp), sat in it, lay in it until the light started to go and I called a halt. She climbed out, covered in mud, but she was exhilarated – and giggling.”

BACK TO WORK, 1956

In February 1956, Lois Smith – Marilyn’s New York publicist – invited Eve to a press conference at the Plaza Hotel. Marilyn was to announce her latest film project, ‘The Sleeping Prince’. Her co-star, Sir Laurence Olivier, and Sir Terence Rattigan, author of the original script, had flown in from London to meet her.

At Smith’s request, Eve arrived early and visited a nervous Marilyn in her dressing room. “Marilyn had always had difficulty before actually tackling a problem,” Eve commented. “Once she started something, she would be totally committed: it was the business of propelling herself into the actual situation that she had to grapple with…So she would vacillate, the minutes passing…”

For Olivier and Rattigan, sitting outside the dressing room, this was the first of many long waits for Marilyn. “At eleven in the morning she wore a black velvet gown with straps the width of spaghetti strips,” Eve wrote. “She looked lovely, her white flesh and blonde hair contrasting with the darkness of her clothes. When I complimented her on the way she looked, she winked at me in the mirror and said, ‘Just watch me.’”

Eve didn’t usually enjoy press conferences. The hotel was “so jammed as to make it almost impossible to work.” But her unusual status as one of the few women in her profession had some advantages. “The newsmen were unfailingly courteous,” she explained. “Invariably a path would be made for me.”

The meeting got off to a slow start, with a stiff, awkward Olivier taking most of the reporters’ questions. But when Marilyn removed her coat, the strap of her dress snapped – and all hell broke loose, with photographers scrambling for pictures of the star ‘en deshabilée’.

Though Marilyn denied it, Eve believed the ‘accident’ was, in fact, deliberate. “Suddenly the atmosphere changed,” she wrote. “(Monroe) had made it fun:

laughter was heard, a safety pin was offered and the press conference was hers. It had gone from a ponderous, humdrum, expected situation to an event

– with a little help from her.”

BETWEEN ENGAGEMENTS

During the late 1950s, Eve chronicled the lives of working-class Italians in New Jersey. A particularly charming shot of some children in a truck was used in an advertisement for Standard Oil.

In 1959, Arnold worked on a film set for the first time, photographing Joan Crawford, who had criticised Monroe’s scanty attire at an awards ceremony just a few years before. Nobody was more surprised than Eve when Crawford stripped off for the camera.

As the Sixties began, Eve photographed the new First Lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, reading to her young daughter. She travelled to Virginia to document the emerging Civil Rights movement.

Back in Hollywood, a new Monroe movie was in the works. ‘The Misfits’ had been written by husband Arthur Miller as a ‘valentine’ to Marilyn. John Huston was to direct, and her co-stars would include Clark Gable and Montgomery Clift.

THE MISFITS, 1960

“I’m thirty-four years old. I’ve been dancing for six months (on ‘Let’s Make Love’), I’ve had no rest, I’m exhausted. Where do I go from here?”

These words evoke Marilyn’s mood when Eve Arnold arrived in Nevada. It was midway through the shoot, and Monroe had just returned from a week’s rest in a Los Angeles hospital, during which time filming had been halted.

Exclusive rights to all still photos on and off the set were granted to Magnum. Inge Morath, Elliott Erwitt and others had already visited the set. Eve intended to spend just two weeks on location, but because of her rapport with Marilyn, she stayed for two months.

“Being a woman helped me to understand her moods and responses,’ Eve said. ‘Also, my being another woman avoided the male-female byplay that my male colleagues tell me is necessary in their sessions to produce intimate pictures.”

“As always where close contact was essential to the personal kind of pictures I wanted to make, I worked without an assistant,” Eve recounted. “Lugging gear, loading film, reading exposures were tasks I could have been relieved of, but an extra person might have unbalanced the precarious equilibrium between us.”

Of all the on-set photographers, Eve was the only one admitted to Marilyn’s inner circle. Towards the end of filming, Eve arranged a party for Marilyn and her entourage, whom she described as her ‘family’.

“Every once in a while she would realise that it was a relationship based on a weekly paycheck and would be concerned lest they became paid courtiers,” Eve wrote. “But they never did. They were fierce in their dedication to her.”

GODDESS IN THE STUDIO

As production came to an end and the crew returned to Los Angeles, Marilyn suggested a publicity photo session to a hesitant Eve. She admitted, “I dislike studio photography and the contrived images that usually stem from this genre, but Marilyn loved posing.”

On the other hand, the benefits were that “a studio session is an autonomous situation – it provides the greatest chance for control. One can plan one’s own lighting, work to one’s own time clock, shoot and reshoot, change the subject’s hair style, add or subtract clothing.”

As an old friend, Allan ‘Whitey’ Snyder applied her foundation, Marilyn looked around and said, “Whitey, remember our first photo session? There was just you and me – but we had hope then.”

Monroe revisited her pin-up days in a bikini, toyed with a feather boa, and reclined in a satin slip. Perhaps the most memorable sequence showed her nude beneath the sheets – a scenario she would recreate in two later sessions (Kirkland, Stern), to very different results.

For Marilyn, Arnold believed, “Being photographed was being caressed and appreciated in a very safe way. She had loved the day and kept repeating that these were the best circumstances under which she had ever worked.”

UNRETOUCHED WOMAN

Soon after Marilyn left for her Manhattan apartment, Clark Gable died of a heart attack. Days later, the Millers’ separation was announced. When Eve visited Marilyn at home, gangs of reporters were camped outside the building.

Marilyn was deeply upset by Gable’s death. She had idolised him as a child, and throughout the ordeal of ‘The Misfits’, he treated her with kindness and respect. Monroe also recommended Eve to Gable, and she was the only photographer to record the filming of their bedroom scene.

Marilyn confided to Eve that as a little girl, moving between foster homes, she would dream that Gable was her father. “This tale she told while sitting with a set of proof sheets and a red grease pencil in front of her, editing pictures of herself playing a love scene with Clark Gable. She looked pensive for a moment, sighed and came up with another of her ‘can you imagine’ sentences: ‘Can you imagine what being kissed by him meant to me?’”

Monroe had full approval on all the pictures of her taken during the ‘Misfits’ shoot. Over the next week, she and Eve worked through the many negatives and contact sheets. Lee Jones, Eve’s editor at Magnum, thought the actress was “putting us through as many hoops as she could get us to jump. I, who knew her better and had fairly extensive dealings with movie actors, simply took it as what it was – pure Marilyn. She was distracted, wary, as though waiting for a telephone call that never came.”

As their work continued, Eve demonstrated to Marilyn the process of editing a photo feature. “She was quick and perceptive,” Eve commented, “would listen when I explained why a certain picture or situation was necessary, and would concur if she was convinced. If not, we would battle until one or the other backed down.”

“As the days passed,” Eve remembered, “it was evident that Marilyn was enjoying herself.” She even offered Eve a chance to take more photos, which she declined. “I wanted to photograph her at some future time on some happier occasion – a new film, a new man…who could guess what surprises might be in store for her?”

THE LAST GOODBYE

In July 1961, Marilyn was admitted to New York’s Polyclinic Hospital for gallbladder surgery. It would take her many months to recuperate from this serious operation. Nonetheless, as she left the hospital in a wheelchair, Marilyn was mobbed by the paparazzi.

Nonetheless, Marilyn arranged a photo-shoot with Eve at her home later that day. It was a favour to Kenneth Battelle, ‘hairdresser to the stars’, who was to be featured in ‘Good Housekeeping’ magazine.

“She looked fresh and rested, and she and Kenneth played up for the camera, she teasing him about his showing the more photogenic side of his face,” Eve observed. “We did just one roll of film. It was a simple photo and I did not want to tire her.”

As Eve left, she was approached by a gaggle of reporters, asking what it was like to photograph Marilyn.

In May of 1962, Eve was once again contacted by Marilyn, who was preparing to sing Happy Birthday to President Kennedy at New York’s Madison Square Garden. Eve had only just returned home, and declined the opportunity to cover what turned out to be a memorable moment.

Three months later, Marilyn died. In a 1987 documentary, ‘Eve and Marilyn’, Arnold spoke of her deep regret at having missed her final opportunity to work with Monroe.

APPRECIATING MARILYN

The publication of ‘Marilyn Monroe: An Appreciation’ in 1987 confirmed Eve Arnold’s status as one the star’s finest photographers. Her accompanying text shows personal insight into Marilyn’s exceptional, and sometimes overlooked skills as a model.

“Over the years I found myself in the privileged position of photographing someone who I had first thought had a gift for the still camera and who turned out had a genius for it,” Eve wrote. “I never knew anyone who came close to Marilyn in natural ability to use both photographer and still camera. She was special in this, and for me there has been no one like her before or after. She has remained the measuring rod by which I have – unconsciously – judged other subjects.”

Most actors are uncomfortable before the still camera, Arnold noted, but with Marilyn the opposite was true. “She didn’t have to learn lines as she did for her movies,” Eve commented. “She could let her imagination range freely without concern for consistency or continuity, she could be a different Marilyn for each photographer or each frame of film.”

Whereas in her film roles, Marilyn was often typecast as a ‘dumb blonde’, as a model “she could call the shots, dictate the pace, be in control.” Even in her early ‘cheesecake’ poses, or with more experienced photographers like Eve’s old mentor, Richard Avedon, Monroe’s joyful, innocent persona transcended cliché.

“No matter how the photographer tried to use her in terms of his own personality and style,” Eve remarked, “it is always she who imposes herself to have the final look.”

Marilyn’s approach – honed by years of experience – was extremely subtle. “She had learned the trick of moving infinitesimally to stay in range,” Eve explained, “so that the photographer need not refocus but could easily follow movements that were endlessly changing.”

But although Monroe knew the tricks of her trade, she was never calculating. “It didn’t always work, and sometimes she would tire and it was though her radar had failed,” Eve acknowledged. “But when it did work, it was magic. With her it was never a formula; it was her will, her improvisation. She captured the imagination and heightened the atmosphere.”

Arnold, also self-taught, related to Marilyn’s intuitive style. “We were both gamblers,” she reflected. “We both trusted ourselves and each other to carry us through.”

“Our ‘quid pro quo’ relationship, based on mutual advantage, developed into a friendship,” Eve wrote. “The bond between us was photography. She liked my pictures and was canny enough to realise that they were a fresh approach for presenting her – a looser, more intimate look than the posed studio portraits she was used to in Hollywood.”

But working with Marilyn presented unusual challenges. “A camera anywhere near her would bring out a mob,” Arnold remembered, adding, “The idea of the candid shot was impossible with her. She always knew – as though, wherever she was, whether in a dressing room, resting on a plane or walking in the desert, her own built-in mechanism sensed the camera and responded before the first click was heard.”

Though sympathetic, Arnold resisted becoming a ‘mother figure’ to Marilyn. Those who did, like Paula Strasberg, were often accused of exploiting her. “She would exhaust herself – she never held back, she never learned to save herself.”

Nonetheless, Monroe was at her most creative when being photographed. “If it is true, as some has said of her, that all her life she pursued a search for a missing person – herself –“ Arnold mused, “then perhaps Marilyn, a creature of myth and illusion, found herself not in the fleeting film image, but in the photograph, which would seem to give her concrete proof of her being.”

Some people today want to feel sexy in photos too, and end up taking garcinia cambogia extract from random places.

IN RETROSPECT

In late 1962, Arnold moved to London to be near her son, Frank, who had enrolled at an English boarding school. They arrived just as the coldest winter in a century began. “We were not used to the gloom,” Eve admitted. “We were accustomed to overheated rooms and changing seasons that brightened the year…The endless grey and chill days of England seemed like a punishment and added to our sadness at the sudden changes in our lives.”

One of the last assignments she completed before leaving the US was a profile of Malcolm X and the Black Muslims. Though ‘Life’ considered the subject matter too controversial, the photos were published in ‘Esquire’, and syndicated worldwide.

Throughout the 1960s and 70s, Arnold worked frequently on stories for the ‘Sunday Times’ colour supplement. Eve’s editor, Harold Evans, agreed that her time on any project should not exceed six months per year, so that she could spend time with her son.

“By then Eve was established as a key member of the magazine team alongside Snowdon and Don McCullin,” recalled her art director, Michael Rand. “Immensely versatile, her input was a surprising mix of grit and glamour and that was her strength.”

At the height of the Cold War, Eve made two long trips to the USSR in 1965 and ’66, and her wealth of pictures spanned thirty features. Then in 1969-70, she made a documentary, ‘Behind the Veil’, exploring the daily lives of women in the Middle East.

In the mid-1970s, Eve befriended the teenage Beeban Kidron, who became her assistant for a time. “Before she went on trips Eve would fill notebook after notebook with research and thoughts about the place she was going,” Kidron (now an acclaimed film director) told Brigitte Lardinois in 2009. “Her return would be a whirlwind of developing, sorting and printing – never jet-lagged, she would often work into the night.”

A harrowing trip in 1973 made Eve ill for months afterward. Devastated by the poverty and racism she had witnessed, she told the BBC’s John Tusa, “I came back from four months in South Africa, absolutely shattered. And my GP sent me to a heart man, and I went, and he prescribed something, I came back, and still it went on for months. And he said the only way I can describe it, is that you are suffering from a broken heart. It was such an emotional reaction. But it was a hellish time for everybody in South Africa.”

In 1979, aged 67, Eve embarked on another ambitious project. Published as ‘In China’, her best-selling book “captured a vast nation on the brink of momentous change.” Her other books include ‘Unretouched Woman’ (1976); ‘The Great British’ (1991); a memoir, ‘In Retrospect’ (1995); and ‘Film Journal’ (2001).

During the 1990s, Eve – then in her eighties – became a “very active” vice-president of Magnum Photos. In 2003, she was made an OBE by Queen Elizabeth II (whom she had photographed in the late 1960s.)

“Photographs are not made in a vacuum,” Arnold wrote in 1987. “The person before the lens is inseparable from the process.” Perhaps it was Eve’s compassion, as well as her unflinching eye, that made her such an outstanding photographer, of Marilyn Monroe and many others.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/1″][vc_column_text]