On July 19, 1946, a little-known model and aspiring actress called Norma Jeane Dougherty took her first screen test at Twentieth Century Fox. Cameraman Leon Shamroy later recalled, ‘I thought, this girl will be another Harlow! Her natural beauty plus her inferiority complex gave her a look of mystery… and she

got sex on a piece of film like Jean Harlow.’

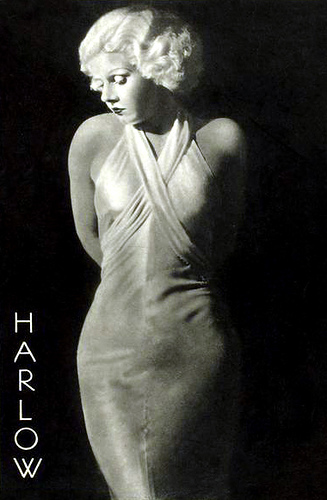

Jean Harlow, to whom the young Marilyn Monroe was often compared, was born in 1911 in Kansas City, Missouri. The daughter of a wealthy, upper middle- class dentist, Mont Clair Carpenter, young Harlean’s first name was an amalgam of her blonde, attractive mother’s – Jean Harlow.

‘Mother Jean’ was a smart, ambitious woman, and soon tired of her kindly but staid husband. She lavished her affection on ‘The Baby’ instead, determined from the outset that Harlean should lead the high life she craved for herself. In 1922, Jean divorced Mont Clair, who would see his daughter only once more.

After a failed attempt to launch an acting career in Hollywood, Mother Jean returned with Harlean to Kansas City. In 1925, Harlean narrowly survived a bout of scarlet fever. Then in 1926, she met Chuck McGrew, aged nineteen and soon to come into a large fortune. A year later the teenage sweethearts eloped to Los Angeles. Accustomed to obedience from her good-natured daughter, Mother Jean was furious at being cut out of Harlean’s life so prematurely. But Jean had also remarried that year, to Marino Bello, a handsome and outwardly charming conman whom Harlean detested.

When Harlean came to Los Angeles, Norma Jeane Mortenson was just a year old, and living with a foster family on the outskirts of the city. Her mother, Gladys, worked as a film technician and it has often been stated that she named her daughter after both Harlow, and the silent film star Norma Talmadge. This

is unlikely, as Harlean was still unknown and had yet to appear in a film. It now seems that Norma Jeane was actually named not after an actress, but the child of a couple Gladys had once worked for.

Norma Jeane would grow up in near poverty with a series of foster carers. She never knew her father, and Gladys was committed to a mental institution when Norma Jeane was seven years old. Whereas ‘Mother Jean’ was a dominant presence in Harlean’s life, Gladys was notable mainly by her absence. ‘She was a

pretty woman who never smiled,’ Marilyn wrote in her 1954 memoir, ‘My Story’. ‘When I think of her now my heart hurts me twice as much as it used to when I was a little girl. It hurts me for both of us.’

Monroe was first dubbed ‘the new Harlow’ when she was still a mere starlet. She later admitted that Harlow was one of her favourite actresses, and that she had first seen Harlow’s films as a child. ‘I had platinum blonde hair and people used to call me ‘tow-head’’, Marilyn recalled. ‘I hated that and dreamed of having golden hair…until I saw (Harlow), so beautiful and with platinum blonde hair like mine.’

Marilyn’s mother Gladys was also a keen movie fan, and decorated her home all white, a style much in vogue at the time. Jean Harlow also favoured white, bias- cut silk dresses, and she too furnished her homes in white. It remained Marilyn’s own favourite colour throughout her life, highlighting her pale skin and

platinum blonde hair.

Grace Goddard, a family friend who became Norma Jeane’s legal guardian after Gladys’s breakdown, was also a Harlow fan. Her co-worker, Leila Fields, commented, ‘If it weren’t for Grace, there would be no Marilyn Monroe…Grace raved about Norma Jeane as if she were her own. Grace said Norma Jeane was

going to be a movie star. She had this feeling. A conviction…’

Back in 1928, Harlean took a screen test at a friend’s suggestion, and began working as an extra at Twentieth Century Fox. It gave her a feeling of independence but it is unclear if she really envisioned a future in acting at that point. However, Mother Jean was now living in Hollywood with her dissolute

husband in tow, and her dreams of stardom were focused on Harlean, who signed her first contract under the name of ‘Jean Harlow’. Norma Jeane would later adopt her mother’s maiden name, Monroe, as her stage name. (‘Marilyn’ was inspired by actress Marilyn Miller, at the suggestion of Ben Lyon, who had long

ago starred in ‘Hell’s Angels’ with Jean Harlow.)

Baby Jean served a tedious apprenticeship of bit parts in unmemorable movies. She had no prior training or experience, and producers were slow to recognise her potential. Marilyn Monroe would also tread a long and uncertain path to success.

After a time, Jean began to win bigger, if not necessarily better parts. In ‘Double Whoopee’, she walks into a hotel lobby, unaware that the doorman (Stan Laurel) has slammed her dress in the door, and arrives at the reception desk wearing just a see-through slip. In ‘The Saturday Night Kid’(1929), Jean Harlow

played another minor role, in a dress too small for ‘It Girl’ Clara Bow. Warming quickly to Jean, Clara insisted on being photographed with her younger co-star. Years later, Marilyn would also benefit from the generosity of a more established actress, Betty Grable. ‘I’ve had mine, honey,’ Grable told her when they

worked together in the 1953 comedy, ‘How To Marry A Millionaire’. ‘Now go get yours.’

Jean Harlow was blonde, strikingly pretty, and had a natural, almost unconscious sex appeal. But the sirens of the twenties were all brunettes – blondes were generally demure, in the style of Mary Pickford. Nonetheless, in 1929 Jean posed nude for the photographer Edwin Bower Hesser. ‘Nudity was rarely seen in those days,’ reminisced writer Anita Loos, ‘and Harlow’s had the quality of an alabaster statue.’ But Jean was not conceited. Actor Lew Ayres described her as ‘a sexy-looking gal who was actually a very nice one.’

Twenty years later, Marilyn Monroe posed nude for a calendar, and when the ensuing scandal threatened to derail her career, she explained simply, ‘I was broke and needed the money. Besides, I’m not ashamed of it.’ Like Jean, Marilyn rarely wore underwear and once said, ‘I’m only comfortable when I’m naked.’

Harlow’s big break came when actor James Hall introduced her to the millionaire Howard Hughes, who then cast her in his aviation epic, ‘Hell’s Angels’. Though her performance was savaged by the press, it made her a star. With Clara Bow’s career on the wane, a new sex symbol was emerging. As the Great

Depression ravaged America, the carefree flapper was replaced by the hard-boiled dame, a so-called ‘laughing vamp’, and it seemed that no one embodied this archetype more vividly than Jean Harlow. She was generally cast as the scheming, promiscuous gold-digger, a character diametrically opposed to her true

nature.

In another parallel with Harlow, Marilyn would also be typecast as a ‘dumb blonde’, and audiences would often confuse her skilled comedic performances with her offscreen personality. Deeply insecure, Marilyn projected an extreme vulnerability which was sometimes misinterpreted as ignorance or weakness. But

she was determined to succeed. ‘I used to think as I looked out on the Hollywood night — there must be thousands of girls sitting alone like me, dreaming of becoming a movie star,’ Marilyn admitted. ‘But I’m not going to worry about them. I’m dreaming the hardest.’

After Mother Jean’s arrival in Hollywood, Jean had drifted apart from Chuck McGrew, to whom she had been close. They finally divorced and Mother Jean regained control of her daughter’s life. Marilyn had also wed at sixteen, to the ‘boy next door’, Jim Dougherty. Theirs was largely a marriage of convenience,

though the couple were happy enough until Jim joined the Merchant Marines. His departure was just the latest in a cycle of abandonments for his child bride, who then turned her energies towards a career in Hollywood.

Unlike Jean, Marilyn had no stage mother behind her, and no Svengali waiting in the wings. It would seem that she engineered her own rise to fame, and desired it more than Jean perhaps did. But the truth may be more complex. ‘All I want is to be loved, for myself and my talent,’ Marilyn once admitted. And

Clark Gable, who worked with both Monroe and Harlow, said of Jean, ‘She didn’t want to be famous, she wanted to be happy.’ For Marilyn, fame was a substitute for the unconditional love that eluded her – but in Jean’s case, work may have been a refuge from her mother’s suffocating love. Neither Marilyn or Jean would find lasting happiness.

Jean’s string of star vehicles began in 1932 with ‘Red-Headed Woman’, a daring sex comedy which fell foul of the censors. Her sexy persona would later be toned down to fit industry guidelines. Several of Monroe’s films were vetted in the same way. But in 1932’s ‘Red Dust’, Jean caused a sensation by being shown

taking a bath in a rain barrel.

‘Dinner At Eight’, Harlow’s most enduring hit, was filmed in 1933. She was part of a prestigious, ensemble cast and her final scene is a defining moment in Hollywood history. ‘I was reading a book,’ she tells Marie Dressler. ‘A crazy kind of book…Do you know that machinery is going to take the place of every profession?’ After a moment, Dressler replies, ‘Oh, my dear. That is something you need never worry about.’

George Cukor, who directed ‘Dinner At Eight’, later worked with Marilyn on ’Let’s Make Love’. ‘(Jean) and Marilyn were quite different’, he commented. ‘But they had this in common; they were both extremely attractive, and they both had the knack of concealing what they knew. The comedy seemed quite natural,

yet they knew exactly what they were doing.’ Like Harlow, Marilyn had impeccable comic timing. ‘Some Like It Hot’ (1959) is widely regarded as a comedy classic, and she excelled in musicals such as 1953’s ‘Gentlemen Prefer Blondes’.

‘Bombshell’ (1933) was a sharp, witty satire on Jean’s own life, where she played a movie star trying to escape her trashy image and entourage of lazy, no-good relatives. She went on to play more sympathetic roles in ‘The Girl From Missouri’ (1934) and ‘Wife Vs Secretary’ (1936), ultimately gaining the critical acclaim she richly deserved. Marilyn Monroe would also prove herself a fine actress in her later career, seeking out less glamorous roles such as the downtrodden Cherie in ‘Bus Stop’ (1956), and holding her own against classically trained actors like Sir Laurence Olivier in ‘The Prince And The Showgirl’ (1957.)

In private, Jean was drawn to older, intellectual men. Like Marilyn, she seemed to seek father figures to replace the actual father she had lost. In 1932 she married MGM producer Paul Bern, who committed suicide just months later. Briefly a murder suspect, Jean was plunged into a messy scandal. Some

speculated that Bern was impotent, others talked of bigamy. To save their star’s reputation, MGM arranged for Jean to marry cinematographer Hal Rosson – a union that also ended after a few months.

Jean was a voracious reader, and under Bern’s tutelage had written a romantic novel, ‘Today Is Tonight’. It remained unpublished until 1965. ‘She’s a girl with lots of love who weakens now and then, but clings to an ideal that finally comes through triumphant’, Jean said of her heroine, whom she based on herself. But

her attempts to bring the story to the big screen were never realised. It seemed that the studios, and perhaps the public, liked Harlow best when she played the sexpot.

Marilyn shared Harlow’s interest in literature, and in collaboration with screenwriter Ben Hecht had written a memoir. Its depiction of her troubled childhood was shocking for its time and Marilyn’s second husband, Joe DiMaggio, was reportedly unhappy with some of the book’s other revelations. Apart from a brief serialisation in an English newspaper, ‘My Story’ was not widely circulated until long after Monroe’s death. And during her four-year marriage to dramatist Arthur Miller, Marilyn agreed to play the sensitive divorcee Roslyn Tabor in his own screenplay, ‘The Misfits’. Roslyn’s character was apparently based on

Marilyn herself. While ‘The Misfits’ was not a runaway hit on release, it is now thought of as one of her best performances.

Some of Harlow’s best work was with Clark Gable, her male counterpart as a national sex symbol, who was later dubbed the ‘King of Hollywood’. They worked together in six films, including her swansong, ‘Saratoga’. Gable was another of Marilyn’s heroes, and they both starred in ‘The Misfits’, the last film either

completed.

Director Clarence Sinclair Bull said of Gable and Harlow, ‘I’ve never seen two actors make love so convincingly without being in love.’ Sound mixer Bill Edmondson recalled that ‘Clark was nuts about The Baby. He just thought the world of her.’

Jean was popular with her co-workers, who valued her as a consummate professional. Spencer Tracy called her ‘a straight shooter if ever there was one.’ Her reputation is starkly different to that of Marilyn Monroe in this respect. Marilyn was habitually late, and stretched her colleagues’ patience to the limit by

demanding multiple retakes. This was perhaps a result of her innate perfectionism, and the depth of her insecurity. However, some actors and directors, unable to penetrate her shyness, thought her behaviour narcissistic.

‘Harlow was always relaxed, but this girl is high-strung,’ Gable said when comparing the two. ‘(Monroe) worries more – about her lines, her appearance, her performance. She is constantly trying to improve as an actress.’

While Harlow was conscientious, and fought for better roles, she may not have been quite so driven as Marilyn was. In fact, Jean might not have pursued her career in movies if Mother Jean had not insisted on her doing so. Furthermore, Jean was less rebellious than Marilyn. Her submissive relationship with her

mother had set a pattern early on in her life. On the other hand, Marilyn walked out on Fox in 1955 and established her own production company. Unfortunately, her business partnership with photographer Milton Greene dissolved in acrimony after just two years.

In 1957, Marilyn confided in Greene about her feeling of empathy with Harlow. As she grew older, the parallels between their lives seemed only to increase. ‘I kept thinking of her, rolling over the facts of her life in my mind,’ Monroe was said to have told Greene. ‘It was kind of spooky, and sometimes I thought, am I

making this happen? But I don’t think so. We just seemed to have the same spirit or something, I don’t know. I kept wondering if I’d die young like her, too.’

Monroe and columnist Sidney Skolsky had dreamed of making a Harlow biopic since the early 1950s, with the confirmed approval of Mother Jean. But when Marilyn read Adele Rogers St John’s script she backed out, reportedly commenting, ‘I hope they don’t do that to me when I’m gone.’ In 1958, Marilyn posed as

Harlow as part of a session for Life magazine. Arthur Miller said she captured Harlow’s spirit, ‘not so much by wit as by her deep empathy for that actress’s tragic life.’

Despite being a generation apart, Harlow and Monroe shared a common enemy – the notoriously catty Joan Crawford. ‘Joan was quite jealous (of Harlow)’, revealed journalist Dorothy Manners. ‘She’d been the sexpot of the MGM lot for years, and then they brought in the Baby.’ Then in 1953, Crawford attacked

Marilyn Monroe’s scanty attire on the night she won a Photoplay award for ‘Fastest Rising Star’. ‘She should be told that that public likes provocative feminine personalities,’ Joan told a reporter. ‘But it also likes to know that underneath it all, the actresses are ladies.’

In later years, Joan mellowed towards her former rivals. She conceded that Harlow was ‘one of Metro’s real biggies, but a more tragic person you can’t imagine.’ On the night after Marilyn’s death, Crawford raged to George Cukor , ‘Dammit, this shouldn’t have happened! …She had all these people on her

payroll. Where the hell were they when she needed them? Why did she have to die alone?’

In the final years of their lives, both Marilyn and Jean Harlow may both have fallen prey to addictions – according to her best biographer, David Stenn, Jean was fast becoming a heavy, if secretive drinker, while Marilyn grew more openly dependent on prescribed drugs. Both women had a history of failed

relationships.

Jean was in love with actor William Powell, her co-star in ‘Libeled Lady’ (1936). But after splitting from Carole Lombard, Powell did not want to settle down with another movie star. Understandably, this made Jean terribly depressed. (Powell would later work with Marilyn in ‘How To Marry A Millionaire’.)

Jean’s image softened as her career progressed, and in 1936 she traded her platinum blonde hair for a more natural ‘brownnette’. Marilyn kept her platinum shade, bleached regularly by Pearl Porterfield, who had previously worked for Harlow. Monroe’s masseur, Ralph Roberts, described the luminosity of her

skin as ‘like cotton candy that could glow in the dark.’ Many of Harlow’s friends have spoken of her radiant complexion, which is instantly evident on screen. Monroe’s director Billy Wilder has noted their shared quality of ‘flesh impact.’

By 1937, Jean’s health was in decline. Photographs show her looking bloated and much older than her twenty-six years. In one of her last public appearances, Jean visited the White House and was introduced to President Roosevelt and his wife, Eleanor. A quarter of century later, Marilyn Monroe would sing Happy

Birthday to President Kennedy at Madison Square Garden, less than three months before her death.

Filming of ‘Saratoga’ was halted when Jean collapsed on the set. A week later, she was rushed to hospital. The cause of her illness was uremic poisoning, and in a time before kidney transplants there was no way to save her. Many rumours have grown around her death, not least the suggestion that Mother Jean, by then

a Christian Scientist, had refused her treatment. In his 1993 book, ‘Bombshell’, David Stenn argued that this was untrue, as Harlow’s prescriptions have since been traced.

Mother Jean was one of many in Hollywood who followed Christian Science. Norma Jeane was also brought up in that faith, though she later drifted away from it. Ironically, her addiction to the painkillers and sleeping pills prohibited by Christian Science would be her final undoing. Marilyn was found dead of an

overdose in 1962, and at thirty-six she was ten years older than Jean at the time of her passing.

Marilyn’s health had been so fragile that she was temporarily fired from her last film, ‘Something’s Got To Give’, though the executives at Fox later re-hired her on a higher salary. Existing footage shows Marilyn looking slimmer than ever before, with an almost ethereal beauty. While ‘Something’s Got To Give’ has

been left unfinished, ‘Saratoga’ was completed using a stand-in for Harlow. Clark Gable said the grisly experience was ‘like being in the arms of a ghost’.

Jean’s funeral was a lavish spectacle, but the outpouring of grief from the Hollywood community was genuine. ‘The day the Baby died, there wasn’t one sound in the MGM commissary for three hours,’ recalled screenwriter Harry Ruskin. ‘Not one goddamn sound.’ William Powell was shaken by the death of his

erstwhile lover, just as Joe DiMaggio was devastated by the demise of his beloved ex-wife nearly thirty years later. Marilyn’s funeral was a much smaller affair, but the tragic circumstances of her death shocked the whole world.

Two films about Harlow were released in 1965, and both were disappointing. One critic likened Carroll Baker’s performance to that of ‘a poor man’s Monroe’. In that same year, Irving Shulman’s scurrilous biography of Harlow was published, to the dismay of Jean’s surviving relatives and friends. In years to come, Marilyn Monroe would also be subjected to an onslaught of dubious kiss-and-tell memoirs, and many films and documentaries of varying quality.

Jean Harlow, the original ‘Blonde Bombshell’, now ranks 22nd in the American Film Institute’s Top 100 stars of all time. She was mentioned in Madonna’s 1990 hit, ‘Vogue’, and as recently as 2004 she was portrayed by singer Gwen Stefani in ‘The Aviator’, Martin Scorsese’s Oscar-winning biopic of Howard

Hughes.

Almost half a century after her death, Marilyn Monroe has perhaps become an even greater legend than Harlow. As Darryl F. Zanuck, head of Twentieth Century Fox, observed, ‘Nobody discovered her – she discovered herself.’ Whereas Marilyn emerged near the end of the studio era, and is often described as

‘the last star’, Jean Harlow was a triumphant product – and also a tragic victim – of its golden age. Nonetheless, Jean Harlow undeniably paved the way for Marilyn and many others, and remains an iconic star in her own right. With her combination of brazen allure and girlish mischief, she was a uniquely American

sex goddess. Other blondes followed her, but none burned as brightly – until Marilyn came along, that is. Like Jean before her, Marilyn’s flame was all too soon extinguished. Both women keenly felt the burden of being sold to the public as objects of desire. As Clara Bow, the first ‘It Girl’, said after Monroe’s death, ‘A

sex symbol is a heavy load to carry, especially when one is tired, hurt and bewildered.’

By Tara Hanks